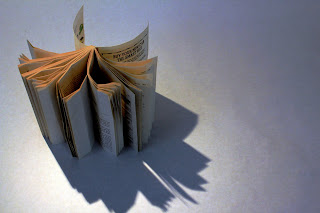

I started this project with dread and of course I blamed Vaughn for making me do something I didn't want to do. As I was working, I did what I usually do and did the cute crap. I found myself frustrated and decided to be a little morbid and a little humorous. Of course I now have stained my hands with red food coloring but I had a lot more fun destroying something. Will I do this again? I don't know, but at least I know that I can figure it out and get some frustration out even if it's not physically tearing someone apart. Lol

I started this project with dread and of course I blamed Vaughn for making me do something I didn't want to do. As I was working, I did what I usually do and did the cute crap. I found myself frustrated and decided to be a little morbid and a little humorous. Of course I now have stained my hands with red food coloring but I had a lot more fun destroying something. Will I do this again? I don't know, but at least I know that I can figure it out and get some frustration out even if it's not physically tearing someone apart. LolTuesday, September 28, 2010

Tiny Things

I started this project with dread and of course I blamed Vaughn for making me do something I didn't want to do. As I was working, I did what I usually do and did the cute crap. I found myself frustrated and decided to be a little morbid and a little humorous. Of course I now have stained my hands with red food coloring but I had a lot more fun destroying something. Will I do this again? I don't know, but at least I know that I can figure it out and get some frustration out even if it's not physically tearing someone apart. Lol

I started this project with dread and of course I blamed Vaughn for making me do something I didn't want to do. As I was working, I did what I usually do and did the cute crap. I found myself frustrated and decided to be a little morbid and a little humorous. Of course I now have stained my hands with red food coloring but I had a lot more fun destroying something. Will I do this again? I don't know, but at least I know that I can figure it out and get some frustration out even if it's not physically tearing someone apart. Lol3D Images

Monday, September 27, 2010

Call for Entries

For anyone interested in submitting work here is a link. The first one is pretty short notice but the second one has more time.

http://www.mplsphotocenter.com/pdfs/AltCFE_WebNEW.pdf

http://www.mplsphotocenter.com/pdfs/UrbanViewRuralSight.pdf

http://www.mplsphotocenter.com/pdfs/AltCFE_WebNEW.pdf

http://www.mplsphotocenter.com/pdfs/UrbanViewRuralSight.pdf

Monday, September 20, 2010

Herman Leonard

Herman Leonard Dies at 87; His Photos Visualized Jazz

By MARGALIT FOX

Published: August 17, 2010

Herman Leonard, an internationally renowned photographer whose haunting, noirish images of postwar jazz life became widely known only in the late 1980s, died on Saturday in Los Angeles. He was 87.

Herman Leonard Photography

Mr. Leonard in a self-portrait in New Orleans in 2004.

A resident of Pasadena, Calif., Mr. Leonard died after a short illness, said Geraldine Baum, the director of Herman Leonard Photography.

Mr. Leonard never set out to document the birth of bebop, though he wound up doing just that. He was simply a young jazz lover whose camera gave him entree into the many New York clubs — the Royal Roost, Birdland, Bop City — whose cover charges he could not afford.

Shot in New York between 1948 and 1956 and afterward in Paris, Mr. Leonard’s work was long known only to jazz buffs. More recently, it has enjoyed a renaissance, collected in books and exhibited worldwide.

“He was a master of jazz, except his instrument was a camera,” K. Heather Pinson, the author of “The Jazz Image” (University Press of Mississippi, 2010), a study of Mr. Leonard’s work, said on Tuesday. “His photographs are probably the single best visual representation of what jazz sounds like.”

Spare and stylized, Mr. Leonard’s work captured a world of shadow, silver and smoke: dark interiors, gleaming microphones and, threading through it all, cigarette smoke that leaped and twined as if it were an incarnation of the music itself.

The artists he shot were titans or soon to be, so renowned that each can be conjured with a single name: Ella, Duke, Dizzy, Billie, Miles, Frank. Carefully lighted and meticulously printed, Mr. Leonard’s photos retained the quality of candids, catching his subjects in moments of powerful intimacy.

One of his best-known portrays Ella Fitzgerald, singing in Paris in 1960, eyes closed in fierce concentration, a rivulet of sweat coursing down her cheek. Another shows Frank Sinatra from behind in lonely silhouette. In a third, a still life, the subject is absent altogether: it depicts sheet music, a Coke bottle, a smoldering cigarette and a porkpie hat hanging atop a saxophone case — the implied, unmistakable essence of Lester Young.

By day, Mr. Leonard was a freelance commercial photographer. By night, he haunted the clubs, whose owners admitted him in exchange for marquee publicity stills. He sold occasional pictures, for $10 apiece, to magazines like Down Beat.

But there was little market for jazz photos then. He put his negatives into a box and forgot about them for nearly 30 years.

Herman Leonard was born on March 6, 1923, in Allentown, Pa., and began taking pictures as a boy. In 1947, after wartime service in Burma, he received a bachelor of fine arts in photography from Ohio University. He worked in Ottawa with the distinguished portrait photographer Yousuf Karsh before opening a studio in New York in 1948.

His visual style was born of necessity: where most photographers would illuminate a club’s confines with half a dozen lights, Mr. Leonard could afford only two. The result, with backlighting piercing inky blackness, lends his work the quality of moonlight.

Mr. Leonard, who shot with a Speed Graphic, was a master printer. Using an old trick of darkroom alchemy, he soaked unexposed film in mercury to enhance its speed in low light. He astonished pharmacists by ordering thermometers in bulk.

After moving to Paris in 1956, Mr. Leonard worked as a fashion photographer. He later moved to the Spanish island of Ibiza, and it was there, in the 1980s, that he pulled from under his bed the box of negatives.

His book “The Eye of Jazz” was published in France in 1985; in 1988, a show of his jazz photos at a London gallery ignited worldwide interest.

Mr. Leonard was married and divorced three times. He is survived by four children — Mikael, from his relationship with Attika ben-Dridi; Valerie, from his marriage to Jacqueline Fauvreau; and Shana and David, from his marriage to Elisabeth Braunlich — and six grandchildren.

Returning to the United States in the late 1980s, Mr. Leonard eventually settled in New Orleans. Then in 2005, Hurricane Katrina flooded his home and destroyed more than 8,000 jazz prints. His negatives were spared: by the time the storm hit, they had been removed to a vault on a high floor of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art there.

A project to digitize and archive the negatives is almost finished, ensuring that Mr. Leonard’s jazz photos will be available for generations. Meanwhile, they can be seen in books like “The Eye of Jazz,” published in English by Viking in 1989; and “Jazz,” to be published in November by Bloomsbury USA.

His work seems destined to endure, colleagues say, for its ability to distill its subjects’ very souls.

“Herman would just catch the moment,” Tony Bennett, a longtime friend, said on Monday. “If he photographed Erroll Garner, that was Erroll Garner; that was his whole spirit.”

By MARGALIT FOX

Published: August 17, 2010

Herman Leonard, an internationally renowned photographer whose haunting, noirish images of postwar jazz life became widely known only in the late 1980s, died on Saturday in Los Angeles. He was 87.

Herman Leonard Photography

Mr. Leonard in a self-portrait in New Orleans in 2004.

A resident of Pasadena, Calif., Mr. Leonard died after a short illness, said Geraldine Baum, the director of Herman Leonard Photography.

Mr. Leonard never set out to document the birth of bebop, though he wound up doing just that. He was simply a young jazz lover whose camera gave him entree into the many New York clubs — the Royal Roost, Birdland, Bop City — whose cover charges he could not afford.

Shot in New York between 1948 and 1956 and afterward in Paris, Mr. Leonard’s work was long known only to jazz buffs. More recently, it has enjoyed a renaissance, collected in books and exhibited worldwide.

“He was a master of jazz, except his instrument was a camera,” K. Heather Pinson, the author of “The Jazz Image” (University Press of Mississippi, 2010), a study of Mr. Leonard’s work, said on Tuesday. “His photographs are probably the single best visual representation of what jazz sounds like.”

Spare and stylized, Mr. Leonard’s work captured a world of shadow, silver and smoke: dark interiors, gleaming microphones and, threading through it all, cigarette smoke that leaped and twined as if it were an incarnation of the music itself.

The artists he shot were titans or soon to be, so renowned that each can be conjured with a single name: Ella, Duke, Dizzy, Billie, Miles, Frank. Carefully lighted and meticulously printed, Mr. Leonard’s photos retained the quality of candids, catching his subjects in moments of powerful intimacy.

One of his best-known portrays Ella Fitzgerald, singing in Paris in 1960, eyes closed in fierce concentration, a rivulet of sweat coursing down her cheek. Another shows Frank Sinatra from behind in lonely silhouette. In a third, a still life, the subject is absent altogether: it depicts sheet music, a Coke bottle, a smoldering cigarette and a porkpie hat hanging atop a saxophone case — the implied, unmistakable essence of Lester Young.

By day, Mr. Leonard was a freelance commercial photographer. By night, he haunted the clubs, whose owners admitted him in exchange for marquee publicity stills. He sold occasional pictures, for $10 apiece, to magazines like Down Beat.

But there was little market for jazz photos then. He put his negatives into a box and forgot about them for nearly 30 years.

Herman Leonard was born on March 6, 1923, in Allentown, Pa., and began taking pictures as a boy. In 1947, after wartime service in Burma, he received a bachelor of fine arts in photography from Ohio University. He worked in Ottawa with the distinguished portrait photographer Yousuf Karsh before opening a studio in New York in 1948.

His visual style was born of necessity: where most photographers would illuminate a club’s confines with half a dozen lights, Mr. Leonard could afford only two. The result, with backlighting piercing inky blackness, lends his work the quality of moonlight.

Mr. Leonard, who shot with a Speed Graphic, was a master printer. Using an old trick of darkroom alchemy, he soaked unexposed film in mercury to enhance its speed in low light. He astonished pharmacists by ordering thermometers in bulk.

After moving to Paris in 1956, Mr. Leonard worked as a fashion photographer. He later moved to the Spanish island of Ibiza, and it was there, in the 1980s, that he pulled from under his bed the box of negatives.

His book “The Eye of Jazz” was published in France in 1985; in 1988, a show of his jazz photos at a London gallery ignited worldwide interest.

Mr. Leonard was married and divorced three times. He is survived by four children — Mikael, from his relationship with Attika ben-Dridi; Valerie, from his marriage to Jacqueline Fauvreau; and Shana and David, from his marriage to Elisabeth Braunlich — and six grandchildren.

Returning to the United States in the late 1980s, Mr. Leonard eventually settled in New Orleans. Then in 2005, Hurricane Katrina flooded his home and destroyed more than 8,000 jazz prints. His negatives were spared: by the time the storm hit, they had been removed to a vault on a high floor of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art there.

A project to digitize and archive the negatives is almost finished, ensuring that Mr. Leonard’s jazz photos will be available for generations. Meanwhile, they can be seen in books like “The Eye of Jazz,” published in English by Viking in 1989; and “Jazz,” to be published in November by Bloomsbury USA.

His work seems destined to endure, colleagues say, for its ability to distill its subjects’ very souls.

“Herman would just catch the moment,” Tony Bennett, a longtime friend, said on Monday. “If he photographed Erroll Garner, that was Erroll Garner; that was his whole spirit.”

A Shot That Captured the Bigger Meaning in Sports

By ROB HUGHES

Published: September 14, 2010 "A Shot That Captured the Bigger Meaning in Sports"LONDON

John Varley/Mirrorpix

Bobby Moore with Pelé at the 1970 World Cup. John Varley, who took the picture, died last week.

The Times's soccer blog has the world's game covered from all angles.

The photograph accompanying this article is one of the best ever taken on a soccer field. The game is over, there is a winner and a loser. Indeed, this image is a symbol of the World Cup, the ultimate prize in soccer, passing from one of these men to the other.

But can you see joy and despair? Or do you see in their touch, their smiles, their eyes something that means so much more than who won and who lost the game? The picture is 40 years old, and there is every chance it will be around for another 40.

It was taken during the 1970 World Cup in Mexico, where England, the 1966 champion, lost the trophy. Brazil won the match, 1-0, in Guadalajara and went on to win the tournament, fielding perhaps the finest soccer team ever.

Above and beyond that, this photograph captured the respect that two great players had for each another. As they exchanged jerseys, touches and looks, the sportsmanship between them is all in the image.

No gloating, no fist-pumping from Pelé.

No despair, no defeatism from Bobby Moore.

Moore, in many eyes the most accomplished English defender ever, died of cancer in 1993. He regarded this photograph as his favorite in a career during which he captained his country 90 times, including the day England won the World Cup.

Pelé, a three-time winner of the World Cup and the most complete player in history, still considers this picture a defining moment in his life.

“Bobby Moore was my friend as well as the greatest defender I ever played against,” Pelé said after Moore’s death. “The world has lost one of its greatest football players and an honorable gentleman.”

Last week, the world lost the third man for whom this photograph meant so much.

John Varley, the photographer, died in his home county, Yorkshire, in northern England. Varley, who was 76, was a news photographer with a sensitive eye for moments beyond the news.

His paper, The Daily Mirror of London, sent him to wars and to natural disasters. And he delivered. In the days when there were no digital cameras, no automatic focus, he had what other photographers described as an instinct for being where things might develop, and a patience to wait for the crucial moment

The Moore-Pelé embrace was such a moment. Look again at the image. Cast your mind back to 1970, when foreign players in the English league — or any league — were rare.

There was at the time a suspicion of black players, ludicrous when one considers that Pelé had been a world star since 1958. It centered on the belief that nonwhites lacked stamina and physical toughness.

This photograph helped break down that prejudice. The blond, blue-eyed Moore and the most wonderful player of his time, Pelé, each stripped to the waist, simply transcended that nonsense.

To take the picture, Varley had taken a sabbatical from his day job.

His contract included a break every four years, and Varley used that to go to each World Cup from 1966 to 1982.

I knew him in the latter years of those assignments, a traveling companion of quiet, droll humor, and, like a lot of photographers of his time, a self-effacing man.

There was no rich living to be made 40 years ago for a specialist sports photographer. Varley’s work shone through the image of a policeman, waist deep in water, carrying a baby to safety during flooding in an English valley.

He took memorable shots of children suffering in the Biafra war — a civil war in Nigeria — as well as a symbolic photograph of a church cross tangled up in rusty barbed wire in the tough Ardoyne district in Belfast during the Troubles of Northern Ireland.

And, again in sports, he looked behind the scenes after a British boxing bout when he snapped a harrowing image of the defeated heavyweight Richard Dunn, his head on the floor of the bathroom shower.

On hearing of Varley’s death, I contacted an American photographer in California. “I have that picture of Pelé and Moore,” he said. “Always admired it, never knew who took it.”

Typical. The man behind the camera is so often anonymous, even in his own trade. But where would we be in this section of the newspaper without men like John Varley?

By ROB HUGHES

Published: September 14, 2010 "A Shot That Captured the Bigger Meaning in Sports"LONDON

John Varley/Mirrorpix

Bobby Moore with Pelé at the 1970 World Cup. John Varley, who took the picture, died last week.

The Times's soccer blog has the world's game covered from all angles.

The photograph accompanying this article is one of the best ever taken on a soccer field. The game is over, there is a winner and a loser. Indeed, this image is a symbol of the World Cup, the ultimate prize in soccer, passing from one of these men to the other.

But can you see joy and despair? Or do you see in their touch, their smiles, their eyes something that means so much more than who won and who lost the game? The picture is 40 years old, and there is every chance it will be around for another 40.

It was taken during the 1970 World Cup in Mexico, where England, the 1966 champion, lost the trophy. Brazil won the match, 1-0, in Guadalajara and went on to win the tournament, fielding perhaps the finest soccer team ever.

Above and beyond that, this photograph captured the respect that two great players had for each another. As they exchanged jerseys, touches and looks, the sportsmanship between them is all in the image.

No gloating, no fist-pumping from Pelé.

No despair, no defeatism from Bobby Moore.

Moore, in many eyes the most accomplished English defender ever, died of cancer in 1993. He regarded this photograph as his favorite in a career during which he captained his country 90 times, including the day England won the World Cup.

Pelé, a three-time winner of the World Cup and the most complete player in history, still considers this picture a defining moment in his life.

“Bobby Moore was my friend as well as the greatest defender I ever played against,” Pelé said after Moore’s death. “The world has lost one of its greatest football players and an honorable gentleman.”

Last week, the world lost the third man for whom this photograph meant so much.

John Varley, the photographer, died in his home county, Yorkshire, in northern England. Varley, who was 76, was a news photographer with a sensitive eye for moments beyond the news.

His paper, The Daily Mirror of London, sent him to wars and to natural disasters. And he delivered. In the days when there were no digital cameras, no automatic focus, he had what other photographers described as an instinct for being where things might develop, and a patience to wait for the crucial moment

The Moore-Pelé embrace was such a moment. Look again at the image. Cast your mind back to 1970, when foreign players in the English league — or any league — were rare.

There was at the time a suspicion of black players, ludicrous when one considers that Pelé had been a world star since 1958. It centered on the belief that nonwhites lacked stamina and physical toughness.

This photograph helped break down that prejudice. The blond, blue-eyed Moore and the most wonderful player of his time, Pelé, each stripped to the waist, simply transcended that nonsense.

To take the picture, Varley had taken a sabbatical from his day job.

His contract included a break every four years, and Varley used that to go to each World Cup from 1966 to 1982.

I knew him in the latter years of those assignments, a traveling companion of quiet, droll humor, and, like a lot of photographers of his time, a self-effacing man.

There was no rich living to be made 40 years ago for a specialist sports photographer. Varley’s work shone through the image of a policeman, waist deep in water, carrying a baby to safety during flooding in an English valley.

He took memorable shots of children suffering in the Biafra war — a civil war in Nigeria — as well as a symbolic photograph of a church cross tangled up in rusty barbed wire in the tough Ardoyne district in Belfast during the Troubles of Northern Ireland.

And, again in sports, he looked behind the scenes after a British boxing bout when he snapped a harrowing image of the defeated heavyweight Richard Dunn, his head on the floor of the bathroom shower.

On hearing of Varley’s death, I contacted an American photographer in California. “I have that picture of Pelé and Moore,” he said. “Always admired it, never knew who took it.”

Typical. The man behind the camera is so often anonymous, even in his own trade. But where would we be in this section of the newspaper without men like John Varley?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)